CONFRONTING TWOMBLY

Artists, especially painters, always have other artists that they are thinking about and reckoning with, the ones whose books get pulled from the shelf in idle moments, who are never far from their thoughts when they’re in the studio. As a painter interested in gesture and process who employs numbers and stencils in an investigation about language and ordering I would routinely be asked about Jasper Johns. The first time it happened, my mind went blank. I hadn’t thought about Johns at all. I was thinking about Chrstopher Wool or Glen Ligon or those great early and underseen Jannis Kounellis works. Roni Horn’s materialization of Emily Dickinson, David Diao’s cataloging of Barnett Newman. Al Held’s alphabet paintings. Johns. Of course. Duh.

This is not the case with Twombly. Richard Serra once called him the bravest artist of the post-war era for taking on Jackson Pollock with nothing but a pencil. There are so many different eras and approaches, evolutions and course corrections, but all coming out of the same practice. If a painter’s gesture is too often referred to as a kind of handwriting, Twombly embedded actual jottings and antique graffiti in the paint surface or expanded it to scrawled fields covering the canvas. As much as other stylistic details move through art history, there’s no other Western artist who has made so much abstract painting out of handwriting. Once I started writing out fragments of text in script, a collision course was set.

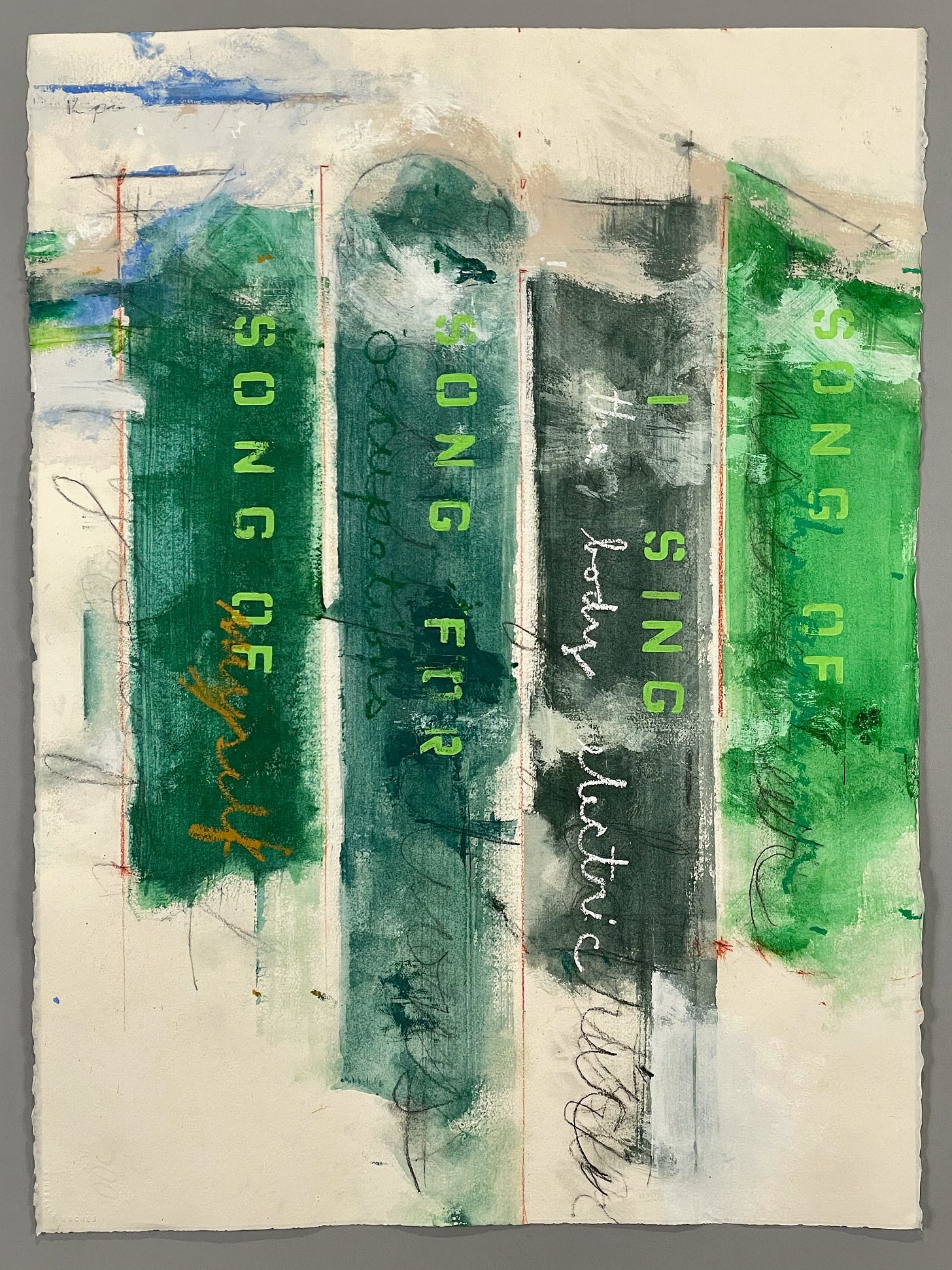

It would have been easier to avoid him, to keep my use of language to stencils, but I wanted to organize and excerpt large bodies of text, and the most immediate way to do that was to take a large piece of paper and start writing, erasing, re-writing. The Annotations series began with the idea of treating drawing and painting as a form of notation; of thinking of a large sheet of watercolor paper as the same as a page in a notebook. An idea generated in a painting would lead to pencil, pen, or conté going onto a fresh page, and the repeated comparison of this against a work in progress started to crystalize my own sensibility.

Like Twombly I use text to focus the work’s content & sources, but unlike him I use it to organize the color and space of the painting. I also often set the text in different orientations (vertical registers are a favorite of mine) or even backwards, anything that might make it harder to read or function more as a visual element. Twombly’s text is usually oriented right side up, but that makes drawings that are closer to writing veer into his orbit. Lists or extend writing in a horizontal register are particularly difficult, and require different approaches in other areas of the work, still sometimes the drawing one makes looks similar to artist that you’ve looked at extensively. Annotation #9 started as an experiment with watercolor that had dried in the tube being cut out and scribbled through puddles on the paper, combined with lines from Whitman and a good deal of open space on the page. The result of course reminded me of Twombly, but not any specific work, so I put it away and moved on to the next drawing. Then several months later while leafing through a Twombly book (not one of the many on my own bookshelf) I came across a work of his that was similar enough to my own effort that it came immediately to mind. If I had known of it, I’m not sure I would’ve left my own finished work untouched, but sometimes you just have to smile, and be glad to have some small company in the studio.

The Annotations drawings are currently on view in “Of Homage or of Hope” at the Adah Rose Gallery in Kennsington, MD.

A review of the show by Mark Jenkins in the Washington Post is here.